A collaborative team from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, the University of Helsinki, the University of Oslo, the University of the Punjab, and others has highlighted ‘remarkable and unexpected differences’ in the distribution of Escherichia coli (E. coli) between Punjab in Pakistan, Europe, and the USA.

The new study, published recently in Nature Communications, also showed that the E. coli strains responsible for many urinary tract infections, and common in countries including the UK, are not found in the Punjab region.

This is the first time the impact of antibiotics on treatment-resistant bacteria has been detailed in Pakistan. It found that while antibiotic use increased the prevalence of certain resistant strains by over 200 per cent, these were generally outcompeted by other strains of E. coli, most likely due to environmental selection pressures resulting from lower levels of sanitation and differences in food hygiene.

Understanding more about the factors that stop these strains from taking hold in the Punjab region could help highlight new ways to reduce the spread of harmful strains in other parts of the world. Ongoing genomic surveillance could also assist in predicting and stopping infection outbreaks.

The bacterium, E. coli is a leading cause of lethal infections worldwide1. Most strains of E. coli are harmless and commonly found in the gut. However, if the bacterium gets into the bloodstream due to a weakened immune system it can cause infections, ranging from mild to life-threatening.

As an added challenge for healthcare providers, antibiotic resistance has become a frequent feature of such infections. Rates of antibiotic resistance in E. coli vary globally and in the UK, over 40 per cent of E. coli bloodstream infections are resistant to a key antibiotic2.

Genomic surveillance can map different strains of E. coli in a region, highlighting which ones are resistant to treatment and tracking those that cause serious infections. Recently, scientists have used these data to investigate factors involved in the spread of drug-resistant bacteria3. However, this research has focused on Western countries such as the UK, Norway, and the USA but antibiotic use and antibiotic-resistant bacteria are present worldwide.

In this new study, a collaboration between the Wellcome Sanger Institute, the University of Helsinki, the University of Oslo, the University of the Punjab, and others, researchers gathered 1,411 rectal and stool samples from 494 outpatients and 423 community members. In some cases, samples were collected before, during, and after the patient took antibiotics to see the impact this had.

The team then used a novel high-resolution deep-sequencing approach developed by co-first author Dr Tommi Mäklin to gain an in-depth genetic understanding of all the E. coli strains in a sample.

The overall distribution differs considerably from studies conducted in Europe and the USA, most notably that endemic strains found in Western countries are not established in Pakistan and the E. coli strains that are leading causes of urinary tract infections in the West are extremely rare.

They also found that apart from the most common strain which is present in both Pakistan and Europe, the top most common strains in Pakistan are rare in Europe and are linked to natural colonisation of the microbiome, not infections. The third most common strain has been found in surveillance in Western countries where it is related to food-borne illness.

Genes that give rise to antibiotic resistance are found in E. coli strains in the Punjab region, with the use of antibiotics increasing the amounts of certain strains by 200%. However, once the treatment was completed, the antibiotic-resistant E. coli strains did not continue to spread.

This suggests that the use of antibiotics created an environment where antibiotic-resistant E. coli had the upper hand, but these strains could not outcompete others once the selection pressure was lost.

Antibiotics are used widely in the Punjab region. However, researchers suggest that due to the differences in sanitation between Punjab and countries such as the UK and Norway, the environmental selection pressures are higher. This means that there is a complex interplay between antibiotic resistance and other traits needed for an E. coli strain to become established in the Punjab region.

Professor Waheed Akhtar from the University of the Punjab said: “This is the first time that an in-depth understanding of E. coli in the Punjab region has been captured and highlights how different environments and healthcare systems can face, and facilitate, a completely different set of bacterial strains and threats. Understanding the bacterial strains present in the Punjab region helps our public health and medical professionals better understand what threats there are in an area, and what could help minimise them. This study shows the importance of having genomic surveillance knowledge and highlights which bacterial strains should be a focus of further research in Pakistan. A future study relating the bacterial genomic data with antibiotic resistance may be an important follow-up to this work.”

Dr Tamin Khawaja, co-first author from the University of Helsinki, said: “During our research, we worked closely with our collaborators in the Punjab region, and saw first-hand that physicians often had less than a minute per patient. This typically leads to them prescribing broad-spectrum antibiotics to ensure as many of the possible causes of sickness are addressed at once. Our research was the first time that the impact of such antibiotic use in the Punjab region was tracked, and shows that this region will require different interventions compared to places such as the UK and Norway. Antibiotic resistance is a global healthcare crisis, one that is often a greater issue in countries with fewer resources. It isn’t enough that the unnecessary use of antibiotics is reduced in western countries, it is in everyone’s best interests to work together and help all countries use antibiotics more rationally.”

Dr Tommi Mäklin, co-first author from the University of Helsinki and visiting worker at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: “E. coli are responsible for infections worldwide, and it’s crucial to understand and track the most dangerous strains if we hope to predict and stop their future spread. Being able to dive into the genetics of different E. coli strains and understand factors that drive their spread asymptomatically is incredibly helpful in the fight against infections. Humans do not exist in a vacuum, and if we could create an environment that is less favourable to dangerous and treatment-resistant bacteria, we could tip the scales in our favour while taking a holistic approach to public health.”

Professor Jukka Corander, co-senior author from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: “Using the innovative deep-sequencing approach developed by Tommi Mäklin, we were able to show remarkable and unexpected differences in the distribution of E. coli between Pakistan and previously studied Western countries. These differences, including the lack of fitness in antibiotic-resistant strains seen in Pakistan that are endemic to the UK and Norway, and those that are the leading causes of urinary tract infections, highlight how E. coli distribution can depend on the environmental factors in an area. They also show that it’s incredibly difficult to predict the success of strains without local data. Therefore, conducting ongoing holistic and worldwide genomic surveillance of E. coli is essential to capturing the full picture of what strains are circulating, how they spread, and what could help stop them.”

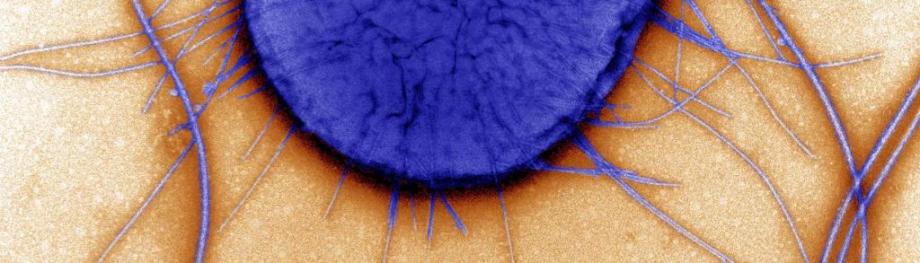

Image credit: courtesy of Wellcome Sanger Institute, David Gregory, Debbie Marshall / Wellcome Images