A major focus will be on Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy (LHON), a disease caused by a gene mutation in the mitochondrial genome that triggers rapid loss of vision in mostly young adults.

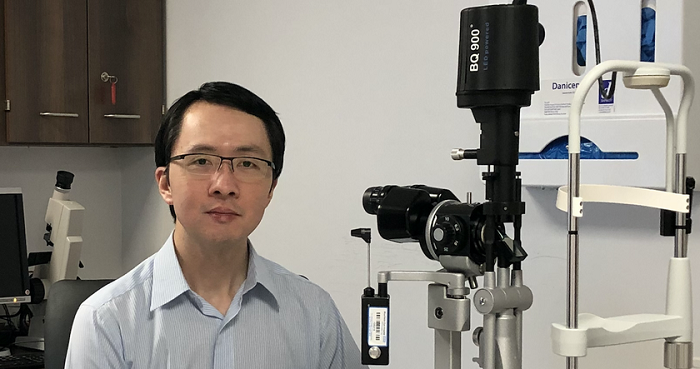

Dr Patrick Yu Wai Man and his team will run the trial at Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge and Moorfields Eye Hospital in London, to better understand LHON and whether gene therapy can help restore sight in some people affected with this condition.

The trial is funded by an NIHR Moorfields Eye Charity Advanced Fellowship and supported by the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

“Your eyes are the greatest camera you’ll ever own and this disease is a devastating blow to people," said Dr Patrick Yu Wai Man, Addenbrooke’s Hospital Honorary Consultant Ophthalmologist.

Dr Yu Wai Man added: “You can go from being fit and well and then suddenly, within weeks, your vision deteriorates rapidly, and you are told you can be registered as blind.

"We know that this disease is hereditary and affects mostly young men. But there are still so many unanswered questions about this condition and we need to find out more in order to identify suitable treatments.

"Our recent research published in Science Translational Medicine is promising, indicating that patients with LHON who have experienced loss of vision for up to one year can benefit from gene therapy. We now want to focus on people who have had this condition for more than one year and that is the basis of our trial.”

LHON and mitochondrial blindness

LHON is caused by genetic mutations in the mitochondrial genome – a unique piece of circular DNA that we inherit from our mother. As a result, healthy cells in the retina are lost, leading to optic nerve damage and severe loss of vision to the point where the person is registered blind. There are currently limited treated options for LHON.

LHON is classified as a rare disease, yet it is estimated to affect at least 1 in 30,000 people in the UK. Although women and children can be affected, the majority of cases occur in young men between the ages of 15 and 35. Most people are unaware that they carry a LHON mutation until symptoms begin to develop with blurred vision or if a family member is diagnosed with this condition.

The reasons why LHON predominantly affects men and why it starts so abruptly remain a mystery.

Launching the trial

The trial will use a form of gene therapy (where a healthy version of the gene is inserted into cells of the retina using a harmless virus) in patients who have lost their vision between one to five years (chronic LHON).

Dr Yu Wai Man said: “We know the disease quickly kills off healthy cells in the retina and we want to try and bring as many cells as possible from the brink to prevent further sight loss and potentially improve vision. In the pilot phase, we plan to recruit 30 patients who will be split into two equal groups.

"One group will receive the gene therapy injections in both eyes whereas the second group will not receive the treatment. The patients will then be closely monitored over two years to see if the treatment improves their eyesight.

"If we are successful, this breakthrough could be life-changing and it will also provide hope to people with visual impairment from other genetic diseases that affect the optic nerve."

Setting sights on further research

Dr Yu Wai Man’s innovative research programme on the inherited optic neuropathies will be made possible thanks to funding from the NIHR in joint partnership with Moorfields Eye Charity.

Dr Yu Wai Man said: “Without this level of commitment for rare diseases from the NIHR, we wouldn’t be able to conduct this kind of trial to try and save people’s sight.

I’m very excited about what we’re going to learn and achieve in the next few years working closely with patient organisations. We may not be able to restore normal sight 100%, but if we could improve vision enough to have a positive impact on someone’s quality of life, that is the most important thing.”

Find out more information on the NIHR Fellowship Programme