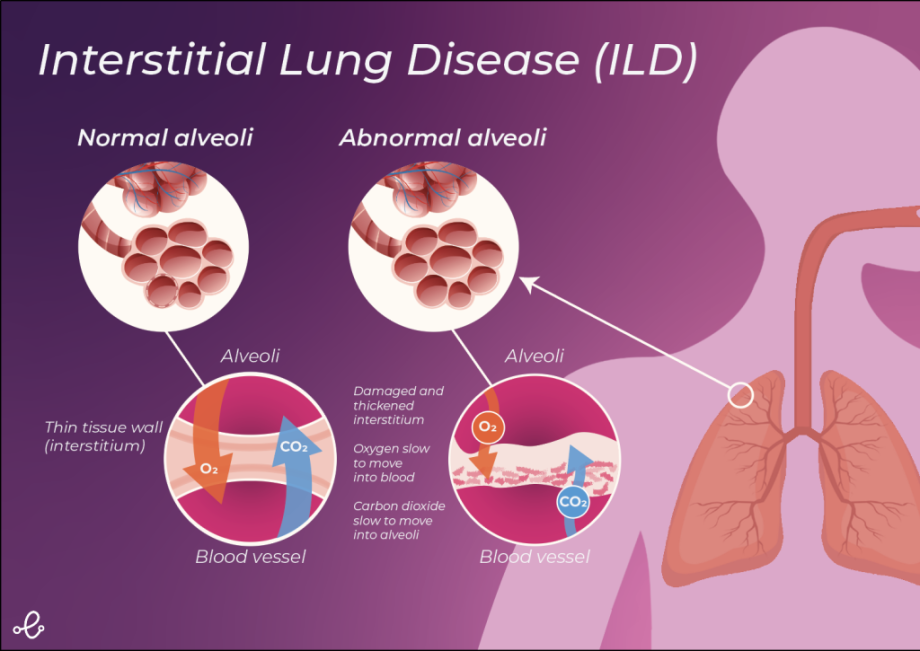

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is an umbrella term used to describe a group of highly variable restrictive lung diseases, which are characterised by inflammation and pulmonary fibrosis (scarring of the lungs). These diseases primarily affect the lung interstitium, the tissue and the space surrounding the lung alveoli (air sacs). The most common ILDs forming part of this group are idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and sarcoidosis.

Scar tissue formation in ILD is usually progressive and irreversible. Over time scar tissue formation causes the lungs to stiffen, restricting lung expansion and hindering oxygen uptake. This leads to the characteristic symptoms of the disease which include shortness of breath following exertion, dry cough, chest discomfort, weight loss and fatigue. The non-specific nature of ILD symptoms often leads to misdiagnosis and missed opportunities to intervene early and delay disease progression.

Delays in diagnosis can have a significant impact on the sufferer's quality of life, cause serious complications, and lead to preventable early death. This article will provide an overview of our current understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying the development and progression of ILD and the strategies being employed to treat and manage the condition.

Mechanisms Underlying ILD

The pathogenic mechanisms underlying ILD are complex and still poorly understood. For many ILDs, no known cause has been established and these are termed idiopathic. However, for some ILDs, some potential causes have been identified including genetics, smoking, infections, certain medications and treatments (e.g. chemotherapy drugs, radiation therapy), gastrointestinal reflux disorder (GERD), autoimmune and connective tissue disorders (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, lupus) and environmental or occupational exposure to hazardous substances [1].

Lung fibrosis undoubtedly plays a key role in the pathogenesis of ILD. It is currently understood that fibrosis in ILD occurs in response to tissue injury and as a result of aberrant wound repair [2]. Fibrosis involves a diverse range of different cellular and molecular processes including fibroblast proliferation and migration, myofibroblast differentiation and extracellular matrix deposition [2]. These events lead to distortion of the lung architecture and the characteristic loss of pulmonary function seen in ILD patients [2].

Another common feature of many ILDs is inflammation and many forms of ILD are known to be triggered by inflammatory events, such as infections or hypersensitivity [2]. However, it is still a matter of debate the extent to which inflammation contributes to fibrosis as lung inflammation does not always lead to fibrotic remodelling, and fibrosis can also occur in the absence of inflammation [2]. Therefore, the exact role of inflammation in fibrosis in ILD is currently unclear.

ILD Progression

ILD is a progressive disease characterised by worsening fibrosis and increasingly severe respiratory symptoms. However, the rate at which fibrosis occurs is highly variable with some patients remaining stable for long periods while others progress relatively quickly.

Sufferers may also experience a sudden worsening of ILD symptoms termed exacerbations. ILD exacerbations are associated with declines in lung function, high rates of hospitalisation and mortality [3]. Often the exact cause of ILD exacerbations is unknown however some potential causative factors may include viral infections, air pollution, drug toxicity, procedures such as bronchoscopy or VATS, and microaspiration [3].

Strategies for the Management of ILD

There currently is no cure for ILD and therefore management of the disease is mainly focused on controlling symptoms and slowing disease progression. Improperly managed ILD is associated with a poorer quality of life and earlier mortality. It is also associated with an increased risk of life-threatening complications including heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, and respiratory failure [4].

As part of ILD management sufferers are encouraged to try and stay healthy by observing good self-care [5]. Those self-care strategies that may be of benefit in the management of ILD include stopping smoking, exercising regularly, eating a healthy, balanced diet, maintaining a healthy mind, ensuring they receive appropriate vaccinations, avoiding infections and seeking appropriate care when necessary [5].

The management of ILD also usually involves the use of pharmacological treatments such as corticosteroids (e.g. prednisone) to reduce the inflammation and anti-fibrotic medications (e.g. nintedanib and pirfenidone) to slow lung fibrosis and disease progression [6]. Those non-pharmacological treatments which are also being utilised include supplemental oxygen, pulmonary rehabilitation and in some rare cases lung transplantation [6].

It is important that ILD patients are routinely monitored for signs of deterioration so disease management strategies can be adjusted appropriately. This usually involves carrying out repeat pulmonary function testing (PFT) [6]. Patients with ILDs are known to exhibit reduced forced vital capacity (FVC), reduced total lung volume, and reduced diffusing capacities [6]. Consequently, PFT should include spirometry, lung volumes, and the diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) testing [6].

Undoubtedly, more research is needed to unravel the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the development and progression of ILD. New insights in this area will aid in the early diagnosis and tracking of ILD through easy to use digital solutions which can increase the effectiveness of intervention and have a measurable impact on patient outcomes. It will also likely lead to new strategies that can help treat ILD and give hope to those suffering from this terrible disease.

References

[1] Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Statement: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Evidence-based Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824.

[2] Glasser SW, Hardie WD, Hagood JS. Pathogenesis of Interstitial Lung Disease in Children and Adults. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2010;23:9–14.

[3] Drakopanagiotakis F, Markart P, Steiropoulos P. Acute Exacerbations of Interstitial Lung Diseases: Focus on Biomarkers. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:10196.

[4] Singh P, Ali SN, Zaheer S, et al. Cellular mechanisms in the pathogenesis of interstitial lung diseases. Pathol Res Pract [Internet]. 2023;248:154691. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0344033823003916.

[5] Lee JYT, Tikellis G, Glaspole I, et al. Self-management for pulmonary fibrosis: Insights from people living with the disease and healthcare professionals. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105:956–964.

[6] Berger K, Kaner RJ. Diagnosis and Pharmacologic Management of Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Disease. Life. 2023;13:599.